Vision Jet: Check Ride Day

Type Rating: Check Ride Day

By: John Fiscus

This is it! The big day is here. You’ve worked hard and grown in both skills and knowledge and you’re ready to demonstrate your skills. The crew at Cirrus has done this hundreds of times – you’re in good hands.

First, it’s ok to have a bit of nerves. It happens to literally all of us: pilots with dozens of type ratings, military fighter pilots, instructors – we all feel it. Take your time with your answers and don’t rush when you’re flying – this is *your* check ride and it happens at your pace.

The test itself is straight out of the ATP (Airline Transport Pilot) ACS (Airman Certification Standards) and it doesn’t have much in the way of surprises. It is, however, written in a slightly less than user-friendly format because it’s a legal document. This article isn’t a legal document so I’ll break things down more clearly below.

The ride itself follows a familiar format where you’ll do an oral quiz with the examiner (complete with a walkaround on a real aircraft) and a flight test. The oral should take an hour or so and cover all the things you’ve been studying in the last two weeks (and more if you did it right). The entirety of the flight portion of the test is done in the full motion simulator and it’ll take a little over 2 hours to complete.

Ground Discussion

This part is going to cover all those systems, limitations, emergency memory items, charts, and SOPs that you’ve learned during ground school. Your examiner will have given you a cross country to come prepared to discuss and you’ll use that as a kind of starting point for diving into the knowledge areas.

The oral is not exactly open book – I’ve had some people come with that mistaken understanding but it’s worth describing what I mean here. You’ll open the book, of course, but it’s to look at charts and perhaps to pull up a diagram that you’re describing to your examiner. But what can’t you look up? Limitations and memory items, basic pilot knowledge IFR items, and pretty much anything that you’d need to know while in flight. Also, the book can’t substitute for understanding. Pointing at a diagram and saying, “That’s the PRSOV,” is not what the examiner is asking for. They’re going to follow your statement with something like, “Good. Describe what it does for me.”

The standard is not perfection, but there are some deal breakers. If you don’t know how or why you’d abort an engine start or what the flap limitations are when you’re in icing, for example, you may be in for a rough (albeit short) day. Know as much as you can by heart and, like any oral exam, stop answering the question when you’ve answered the question. Finally, “I don’t know,” is a much better answer than an incorrect guess.

There is no specific time limit on the oral portion of the test but typically it’s about an hour. Passing is based on knowledge, not time discussing things, so you could even finish faster than that if you know your stuff.

Flight Test

At first this will look and feel like all the other flights you’ve taken during the previous week. You’ll get in and get situated, give your passenger briefing, start up and get ATIS and call for your clearance. The examiner isn’t allowed to have too much chit chat with you though – other than acting as ATC they’re really only allowed to talk to you about what maneuver or approach is coming up next. Ask them if you aren’t sure (“Hey, was it the approach to landing stall you wanted to see next?”) but know that they can’t answer questions about how to fly the airplane (“Do I pull the power back to 15% for the setup for this one?”). They’re there to observe you do the tasks within the standards.

Speaking of, what are the standards? They’re not too far off from what you’ve already done in getting your Private and Instrument. For maneuvers, it’s +/- 100’, 10 degrees on headings, 10 knots of airspeed, that kind of thing.

For approaches it’s a bit tighter than your Instrument check ride let you get away with and this is why it was so important for pilots to make sure they’ve beefed up their hand flying game before coming to train for their type rating. The standards on a precision and non-precision approach outside the final fix are just like the Private Instrument standards. Inside the final fix it heats up a bit: Airspeed +/-5 knots, altitude for the MDA +50 and zero below, and your CDI can’t deviate more than ¼ scale away from the center. The good news is the sim will give you no turbulence or gusty winds to mess with your game. The bad news is the sim will give you no turbulence or gusty winds to blame your performance on.

But what will we do? Well, in short:

You’ll have some issues right out of the gate, usually before you even get off the ground. There’s no slow roll into a check ride! If you know your memory items you’re going to be just fine, and you got a sheet for those on Day 1.

You’ll do a departure, a series of maneuvers that includes various stalls, steep turns, unusual attitudes, and flight in a given configuration/speed (like slow flight). You’ll get going on an arrival and then probably have some manner of emergency that includes memory items followed by a written checklist. You’ll have been given a maneuvers guide to study - make sure you know the setups, speeds, power settings, etc. The examiner cannot tell you how to do a maneuver so you’ll have to get those into your brain. The good news is they’re all fairly similar and you’ve had the tools to prepare for this since the start of your training.

Once that’s all done it’s on with the approaches.

There will be a total of four approaches, two precision and two non-precision. You’ll hand fly some and autopilot fly some, go missed on a couple and land on a couple. It’s up to the examiner exactly which approaches you’ll do, but the standards call for two precision and two non-precision. You can expect a hold, some manner of partial panel issue, a go around, and a flap problem. They’re very fair about this and try to spread out these issues around approaches so don’t worry that you’ll be doing an approach partial panel to minimums with a generator failure while in ice with a cabin fire and one hand tied behind your back.

Tips For Success

-When you’re not doing something that specifically mandates that you hand fly, use that autopilot. The examiner can’t exactly prompt you to turn it back on so when in doubt, ask.

-You can hang out between maneuvers for a second. Engage the autopilot and tell the examiner that you’re going to take a breath. That’s fine.

-If you’re in the middle of something while being vectored for an approach and you’re behind, ask for delay vectors. Your controller will just give you headings and fly you around in a box pattern while you work on whatever your issue is. DO NOT proceed inbound while working a problem.

-Use your iPad if you want. You’ll be encouraged to use the charts on the MFD/PFD during training and they’re great tools, but if it’s getting in your way because you’re unfamiliar then go back to the Old Standby. The standards do not stipulate that you use the on screen charts though you’ll want to be familiar with how to get to them.

-If you’re on the ground mid-checkride, like just after the circle to land, take all the time you need to get set up for whatever is next. Three minutes sitting won’t mess anything up but taking off without ensuring you’re ready sure can.

-If you didn’t sleep the night before, are a ball of stress and can’t say your own name clearly, you have the power to wave off. Yes, it may make schedule complications but there’s often some wiggle room. I’m not going to promise what that wiggle room looks like but they’ll work with you. We would all rather you called it off than bust the check ride.

What If?

Nobody likes this topic but almost everybody asks me at one point or another: What if I screw up and bust the check ride? What will happen?

It isn’t the end of the world.

First, they’re not going to let you get that far if they don’t think you can make it through. That said, if you aren’t feeling like you can pass today, raise your hand and say so. This is a collaboration.

But hey, things happen. On the occasions where there ended up being an unsat it’s typically just brain drain, impulsive act, or nerves. If you do end up exceeding the standards on anything, the examiner is required to tell you right then. They won’t keep it a secret until the end of the ride.

“Remember that: If you haven’t been told you’ve failed, you haven’t failed. Don’t let your mind drift and dwell on mistakes you’ve made.

If you haven’t failed you’re passing. Get on with the flight.”

Once the ride is unsat you’ve got a couple of options which you and the examiner will discuss. First, you can stop right there and keep credit for whatever you’ve already done to standards. Second, you could continue with the check ride and do the things you haven’t attempted yet. If you do them to standards, you get credit for them and won’t necessarily have to do them on the retest. The ride is still unsat, but your retest will be a lot shorter. Note that you and your examiner will have to unanimously agree to continue - if they see signs that this is going south fast, they’ll stop the session. If you’re not feeling it, you have the power to stop it too.

As long as you finish this within the next two months, you’re going to keep the credit for anything you’ve already done. While the examiner has final say and therefore the authority to reevaluate you on a task you’ve already successfully performed, it’s fairly rare. Don’t say I didn’t warn you if they ask you to do something again though. Sometimes it’s just natural that you repeat something, like a takeoff. If you forget to bring the gear up you’ll still fail a retest, even though you managed to do it right on all the other takeoffs.

To retest, you’ll need to come down out of the sim, do some remedial training with one of the instructors, and then go with the examiner for the retest. They’ll work with you to try to get this done as efficiently as possible but keep your expectations realistic. You likely will not be retesting on the same day.

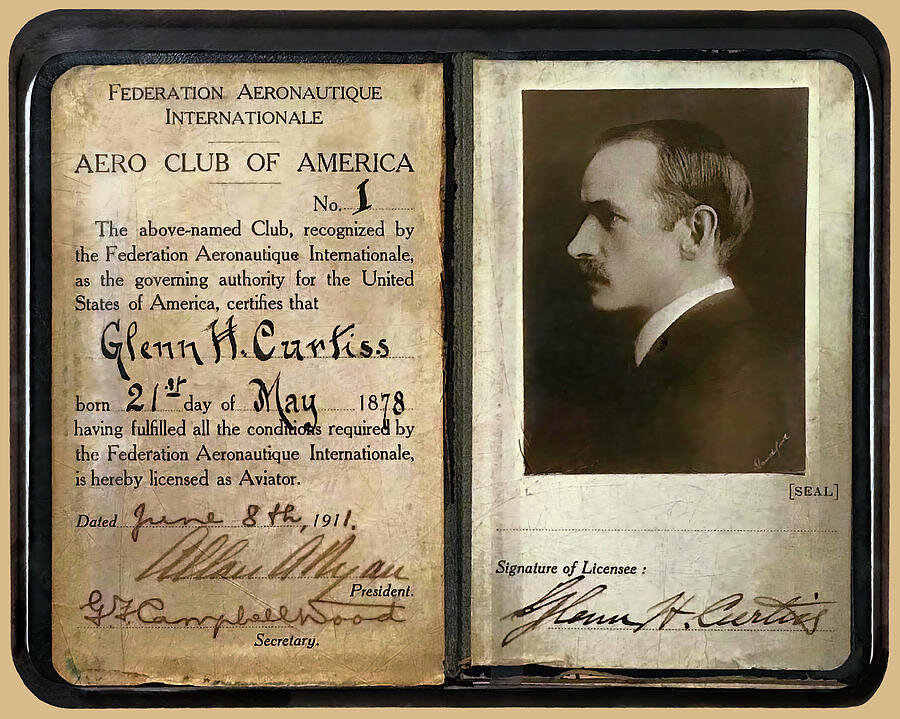

Shiny New Certificate

Congratulations! You’ve put in the work and passed your type rating. You now hold a type rating for a Cirrus Vision Jet and that’s a pretty big deal. We aren’t far in time from when Orville first flew 120 feet but we have come a very long way technologically. You are now part of aviation history and flying a testament to that advancement.

So, now that the fanfare has died down and the ink is dry on your certificate, what’s next? Supervised Operating Experience (SOE) aka mentorship! You’ll need to get 25 hours in the airplane with an instructor before you can operate the aircraft alone, and you’ll definitely want that experience. Our simulator training focuses heavily on approaches and abnormal procedures, but what about all those weird things that happen when you’re flying into someplace busy and the weather is crummy? ATC tells you to keep it fast for the 757 following you into your destination, there’s actually ice on the wing for real, or maybe you’re taking off from a high mountain airport. All these things are dealt with on mentorship.

Come with a plan – we enjoy working in places you’d like to go. If you could see yourself taking your family or friends on a jaunt to someplace special, let’s go there during mentorship. Always been a little leery about ice? Let’s go find some. Got a friend you’d like to have fly along in the back? Let’s make our first flight be to wherever they live and pick them up.

Mentorship will be fun, you’ll get some good learning in, and it’s your first taste of the fruit of your labors. Enjoy!

If you’d like to read more about some of our mentorship adventures and see a few pictures, stay tuned!